Regions of Genocides

In merely a few years during the 1970s, perpetrators of the Cambodian Genocide murdered up to 3 million of their fellow countrymen and caused unimaginable suffering to a great number of others. Members of the Khmer Rouge, the radical political regime behind the terror, invoked a dubious justification of their crimes by alleging that such actions would ultimately improve everyday people’s quality of life through the establishment of a more egalitarian society under communist rule. This purportedly utopian pursuit has left the Cambodian people with a painful legacy, one that they are still struggling to overcome.

Cambodian history was not always so mired in atrocity. In fact, for a long time, visitors recorded being favorably impressed by the region’s promise of an affluent lifestyle to its residents, known as the Khmer. From the 9th through 15th centuries, the Khmer Empire was based in Cambodia and ruled most of southeastern Asia. Its capital city of Angkor boasted a population greater than one million residents, making it for hundreds of years the largest city in the world. Angkor boasted a reputation for prosperity, but was finally sacked in the 15th century, an event that helped usher in generations of hardship. The Spanish and Portuguese soon made attempts to missionize and colonize the region. By the 1800s, the region of Cambodia was locked in a power struggle between neighboring Siam and Vietnam. The French entered at mid-century, and a colonial system soon emerged. While never genocidal, French encroachment was for the people of Cambodia but one more marker on their recent historical downslide. The Japanese invasion during the Second World War saw the weakening of French forces in Cambodia and the installation of Cambodia’s King Sihanouk, whose reign began in 1941. Sihanouk is largely credited with inciting peasants to a successful rebellion against the French after the war, thereby establishing Cambodia as an independent state in 1955.

Cambodia’s independence bolstered optimism within its citizenry. However, that sentiment was soon tempered by the 1962 outbreak of the Vietnam War. Determined to halt the spread of communism, the United States provided huge sums of economic aid to Cambodia and bombed communist bases at its eastern border. Yet Sihanouk hoped to protect Cambodians by endorsing strict neutrality. When he signed a treaty of friendship with Vietnamese communists, the United States halted its military and economic aid, crippling the Cambodian economy. This turn of events helped elevate to prominence the Khmer Rouge, a radical communist group that found the reigning monarchy too moderate. Members of the Khmer Rouge, however, were not the only political players on the rise. In 1970, the Cambodian monarchy was toppled when one of its ministers took power. Lon Nol was eager to regain American support, but was successful only to an extent. While the United States appreciated the regime’s return to its sphere of influence, burgeoning anti-war protests increasingly limited Washington’s options. Under the Nixon Doctrine, the administration once again provided military and economic help to Cambodia, but notably still stopped short of sending additional American soldiers to fend off the communist Vietnamese. The situation in the East grew bloodier. From 1970 to 1973, American bombs totaling hundreds of thousands of tons fell on Cambodia, often annihilating not just communist targets, but also helpless civilians. With the country weakened and undeniably incapable of defending its own people, Cambodia descended into chaos. The Khmer Rouge seized the opportunity to assume power by storming the city of Phnom Penh in April of 1975.

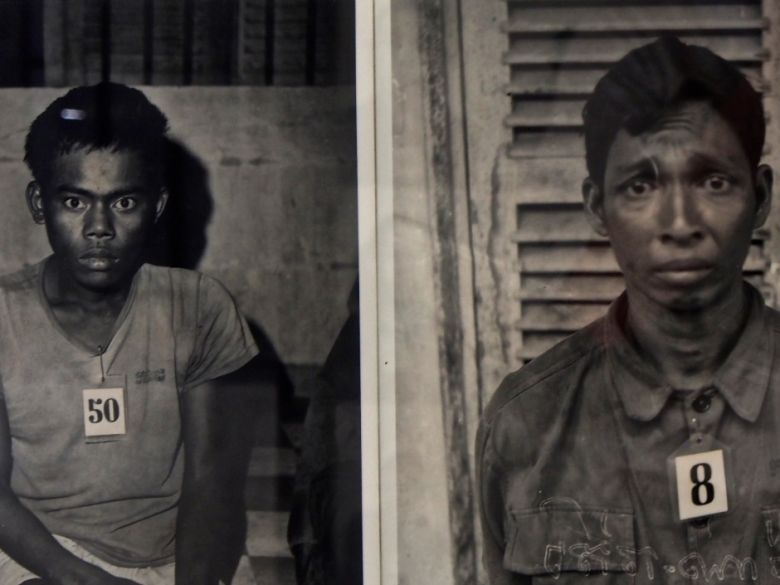

Rule under the Khmer Rouge immediately and intentionally transformed Cambodian life, declaring a “Year Zero” from which point life must completely change. Pol Pot, former schoolteacher and dictator at the head of the newly renamed “Democratic Kampuchea,” put forth genocidal policies that relocated, enslaved, tortured, and murdered enormous numbers of Cambodians. Once in control, the Khmer Rouge evacuated the city of Phnom Penh, moving three million civilians to the nation’s rural fields. The people were made to work long hours of backbreaking slave labor and received little, if anything, to eat. Malnutrition and medical neglect were rampant. When their labor fell short of production goals, men, women, and children were beaten. What became known as “The Killing Fields,” where piles of decaying bodies littered the earth, notoriously bore witness to the genocide. The perversion of familiar institutions helped support the regime’s genocidal policies. In probably the most infamous example, one high school was converted into the S-21 Prison, where up to 20 thousand prisoners were tortured into writing confessions to crimes they had never committed. With this ruse, the perpetrators could maintain some illusion that their practice of mass executions was warranted.

That Cambodia no longer had a system of currency or a market for international trade further hindered its war-ravaged economy and added to a general tone of desperation. But the people’s problems extended beyond harsh economic circumstances and into every facet of life. The regime was fiercely nationalistic and xenophobic. Especially after their history of foreign interference, Cambodians might be seen as justified for harboring such sentiments. However, the Khmer Rouge took that mood to a fanatical extreme. The totalitarian nature of the new government meant that Cambodians were expected to be loyal to the state above all, an ideal that by design worked to tear apart familial bonds. The very notion of individual free choice was systematically demonized by the regime, which also condemned as traitorous any allegiance to more traditional authorities. Foremost among them was a longstanding essential component of Cambodian culture, Buddhism. Deprived of Buddhism’s ancient wisdom for enduring hardships, Cambodians were now even more ill-equipped to survive.

While throwing traditions by the wayside, the Khmer Rouge still assumed something of a reactionary character, at least insofar as it privileged through propaganda the agrarian lifestyle that characterized the earlier Khmer Empire. Only by embracing the simple life of the farmer, it was taught, could Cambodia reclaim its stolen grandeur. The regime made a point to elevate those from rural communities, or “Old People,” over the formerly city-dwelling “New People,” whom it deemed useless. With the peasant lifestyle propped up as the new ideal for virtually everyone, urbanity and learning were actively disparaged, frequently to points of absurdity. Eventually, the simple act of wearing glasses was enough to mark a Cambodian as an intellectual, and thus as an enemy of the regime, deserving death. The Khmer Rouge also targeted for murder potential political rivals, but did not stop there. The sheer volume of executions attests to a policy of widespread victimization and terror. And while ostensibly a communist state, new class distinctions emerged where even young children of Party leaders were placed in positions of authority. Although many other children suffered and died at the hands of the Khmer Rouge, the Party line at least in principle taught that children were morally superior to most of their elders because of the latter’s past associations with corrupt capitalism and religion. In this respect, the Cambodian genocide operated as an orchestrated assault on a civilization’s memory.

By 1979, when Vietnam invaded Cambodia, anywhere from a fifth to a third of the Cambodian population had been murdered by the Khmer Rouge, the vast majority of survivors of the genocide were traumatized and functionally illiterate, and the region was in shambles. Under Vietnamese auspices, Cambodia became the People’s Republic of Kampuchea for a decade, until Vietnam withdrew in 1989. Throughout the 1980s, the Khmer Rouge continued to dominate as much as half of Cambodia, and in 1993 they came terrifyingly close to gaining control of the entire country. The Paris Peace Accords of the early 1990s restored the Cambodian monarchy under Prince Sihanouk, but this conscious move towards normalcy could not mask the wounds of a nation that was still clearly in crisis. International aid to Cambodia accounted for over half of the country’s annual budget. Enormous craters could be seen scattered across a land that remained one of the most underdeveloped in the world - the same land whose civilization had been one of the most advanced in the world several centuries earlier.

The death of Pol Pot and the surrender of the last of the Khmer Rouge soldiers did not occur until the turn of the century, and it was not until 2006 that formal criminal proceedings regarding the genocide began. Four cases began against senior commanders, including the head of the S-21 Prison. Now, nearly four decades after the atrocity, cases are still being brought to court in a sincere if belated effort to foster some sense of justice.

Today’s independent nation of Bosnia and Herzegovina is a recent creation, one chiefly comprised of three different religious groups: the Bosniaks, who are predominantly Muslim; the Serbs, who are Christian Orthodox; and the Croats, who are Roman Catholic. This mix is in large measure a legacy of the Ottoman Empire, which ruled the territories from the 14th to 19th centuries. At the height of its power, the Ottoman Empire brought under its rule various ethnicities, religions, and formerly independent nations; the kingdoms of Bosnia and Serbia are but two examples. The empire extended from southeastern Europe to parts of western Asia and much of northern Africa, but in modern times it showed evidence of decline and was increasingly derided as the “Sick old man of Europe.” Nationalism spread through Europe in the early 19th century, when at great cost the Ottomans faced and eventually defeated a Serbian uprising. Serbia would, however, regain its independence later in the century. The major powers of Britain, France, Germany, Russia, and Austria-Hungary were also eager to dismantle the empire.

Austria-Hungary acquired Bosnia-Herzegovina in 1878, mere decades before a Serbian nationalist assassinated the heir to the Austro-Hungarian throne and the First World War began. The assassin was hardly alone in thinking that political independence for his people would solve their problems. Especially in Central Europe, nationalism gave millions of people hope that they could enjoy a better quality of life and once again take pride in standing tall in the community of nations. WWI succeeded in toppling several longstanding empires, including both the Ottoman and Austro-Hungarian, but still failed to convince most Europeans that a just resolution had been achieved. The immediate postwar period saw the creation of new countries and the drawing of controversial national borders throughout much of the continent.

On one level, it made sense that the newly established Kingdom of Serbs, Croats, and Slovenes – later renamed Yugoslavia – should join together several mainly Slavic peoples who had felt mistreated under the earlier empires, and might each be too small and vulnerable to stand alone. Yet if the new kingdom afforded its citizens greater protection, it was also never designed to offer them full political and economic parity. The Serbians dominated the seats of power, beginning with the monarchy, and aimed to increase their influence and gain territory. To be sure, this was not simply a matter of greed, but rather that most Serbs, like other Europeans in the wake of the war, saw self-rule as their best hope for peace, prosperity, and self-preservation. But Yugoslavia included not just Serbs, but also large numbers of Croats and Bosnian Muslims, as well as smaller minorities, such as Slovenes, Germans, Macedonians, Hungarians, Albanians, and Jews. Several of these groups had once ruled their own lands and refused to accept Serbian governance, particularly as economic hardships grew during The Great Depression. The Second World War exacerbated many of these tensions, with some groups aligning with the Third Reich. At war’s end, Yugoslavia moved towards communism under a new government, but President Josep Broz Tito managed to prevent the country’s descent into the sort of Soviet satellite state status that enveloped other newly communist nations in Europe. Tito also restored some semblance of stability, if not an easy unity between the nation’s various communities. Old tensions continued to simmer not far beneath the surface, however, and matters rapidly deteriorated after Tito’s 1980 death. With the collapse of European communist governments later in the decade, Yugoslavia’s end seemed imminent in the early 1990s.

In 1992, Bosnia and Herzegovina broke from Yugoslavia by declaring independence. Serbs living in that part of Yugoslavia refused to recognize this move, which would make them a minority population, one considerably smaller than the Muslim majority. From the Serbs’ point of view, at issue once again was whether other peoples had a right to rule over them. Under the auspices of ostensibly protecting their people, within weeks Serbian forces with the Yugoslav military took control of two-thirds of Bosnia and Herzegovina and quickly began a genocidal campaign against the Muslim Bosniaks. This involved mass murder; systematic terrorization, including rape; forced relocations, sometimes to prison camps; and the destruction of historically Muslim buildings. The United Nations, reluctant to intervene, avoided calling these actions a genocide, and instead resorted to a more benign label, ethnic cleansing, which refers to the process of merely removing a population from a location to achieve ethnic homogeneity. The UN did send humanitarian aid and established a handful of “safe areas” to which Bosniaks might flee, but under the aegis of only a small and generally ineffective peacekeeping force. Since 1992, Sarajevo, the capital of Bosnia-Herzegovina, had faced intense bombing by the Serbians, and its government had called for more than humanitarian assistance and token peacekeeping efforts from the international community. If the attacks on Sarajevo failed to galvanize the West, those on a smaller, less famous town brought a different reaction.

The terrible and widely reported events in Srebrenica in 1995 are what finally prompted the UN to take decisive measures to halt the genocide. Srebrenica, a town in eastern Bosnia, was a designated safe area that had taken in a relatively small number of Bosniaks. UN peacekeepers were no match when Serbian troops surrounded and then invaded the area. Prisoners were separated by gender: women and girls were loaded onto buses for relocation at Muslim displacement territories, where they were raped, and males aged 12-77 were removed and murdered in what has been deemed the biggest massacre since the Holocaust, at least in Europe. The events at Srebrenica received widespread media attention and were harshly condemned by the outside world. With the characteristics of genocide now apparent, a more persuasive case was made for stronger military intervention from the Western powers. In August 1995, NATO launched three weeks of bombing on Bosnian Serbs, which pressured Serbs throughout the former Yugoslavia to negotiate. Both sides signed the Dayton Accords in Ohio later the same year, formally recognizing Bosnia and Herzegovina as a single country with two states.

In the wake of the Bosnian Genocide, the West has had to come to terms with its responsibilities to justice, remembrance, and prevention. Between 1991 and 1999, when the total population of Bosnia and Herzegovina was a few million people, over 100,000 were murdered, millions were displaced, and thousands remain missing; in order to hide evidence of their atrocities, Serbian perpetrators on several occasions dug up victims’ corpses and buried them anew in places that are hard to find. The International Criminal Tribunal for Former Yugoslavia, the first of its kind since Nuremberg, has charged 160 people with crimes for the period from 1991-2001, resulting in 60 convictions. The trials continue, having been extended through 2016. Serbian Yugoslav leader Slobodan Milošević, whom many people saw as the face of the genocidal campaign against the Bosniaks, was brought before the International Court of Justice, but was never found guilty of the genocide perpetrated by Bosnian Serbs. In 2007, the same court ruled that Milošević had violated the Genocide Convention by failing to act to prevent others’ crimes of genocide or to punish the same perpetrators. By then, he had died in prison.

Rwanda is a small country in central east Africa. Over the course of the short period from April through July of 1994, beneath the cover of an ongoing civil war, extremist members of Rwanda’s Hutu ethnic majority targeted the nation’s Tutsi minority for rape, torture, and murder. Political moderates and some members of the Twa minority were also victimized. To grasp the historical context of the Rwandan Genocide, one must take care to note the role of European colonization in exacerbating tensions between Rwanda’s ethnic groups. Acknowledgment of the importance of colonialism in helping to lay the path to genocide, however, must not be taken to mean that the genocide was inevitable, or that the earlier colonial powers were responsible for choices that were later made by the actual perpetrators in the 1990s.

For most of its history, Rwanda was organized into clans. By the 18th century, several kingdoms had emerged, and the most powerful one was ruled by the Tutsis. Expansion of this kingdom in the 1800s emboldened the ruling Tutsis to force many of the Hutus to serve them. Colonization by the Germans in the late 1800s, and then by the Belgians in the early 1900s, only heightened the problem. Both European powers favored the Tutsis over the region’s other groups. In the period between the world wars, people throughout the Western world paid greater heed to matters of nationalism and race. Keeping with the trend, Belgian laws during the 1930s sought to designate Rwandans as Hutu, Tutsi, or Twa. Mandatory identification cards explicitly marked a person’s identity along these lines and served as a tool for discrimination. Frequently, it was the Hutus who most felt the brunt under this system.

After the Second World War, Rwanda, like neighboring Burundi, remained part of Belgium’s sphere of influence as a United Nations Trust Territory. However, in an era that saw the dismantling of European colonial empires around the globe, as well as rapid population growth in Rwanda, many Rwandans demanded immediate recognition of their full political independence from European influence. Even as this push for independence gained momentum, not all Rwandans united behind the cause: several Hutus judged it more prudent that they work immediately to topple the longstanding hierarchical socioeconomic system, which still privileged the Tutsis. This tension exploded during the 1959 Rwandan Revolution, wherein Hutu forces attacked and massacred Tutsis, many of whom fled to safety outside Rwanda. Changes now came quickly. In 1961, Belgium agreed to the revolution’s demand for the abolition of the Rwandan monarchy, and the following year, Rwanda achieved independence under a Hutu-led government. Violence continued to plague the young country, with the Hutu-dominated regime regularly under attack from refugee Tutsi military forces. A military coup in 1973 brought another new government, led by Juvénal Habyarimana, a Hutu. His administration to some extent managed to reduce the frequency of violent outbursts between the Hutus and Tutsis, but still achieved no lasting reconciliation.

Rwanda plunged into civil war in 1990, when refugee Tutsis and their allies under the banner of the Rwandan Patriotic Front launched a more aggressive military campaign. The government tried to use this campaign to demonize all Tutsis and massacred Tutsi civilians on several occasions over the next few years. Although the United Nations stepped in to try to negotiate a ceasefire and a peace agreement, the plan collapsed in 1994, when a plane carrying the Hutu presidents of Rwanda and Burundi was shot down. This prompted several angry Hutus in both countries to call for their countrymen to murder the nation’s Tutsis. Indeed, Hutu extremists in Rwanda had been preparing for such an opportunity through the propagation of hate speech on the radio, the formation of interhamwe (militia groups), and the dispersal of machetes

Starting in April 1994, within a three-month period, more than 800,000 Rwandans were murdered because of their ethnic identity. Women were systematically raped, in many cases right in front of their children. Many moderate Hutus, who attempted to aid their fellow Rwandans, were brutally killed. Terrified Tutsis sought refuge in churches, expecting asylum would be granted in the predominantly Christian country; instead, several churches became sites of mass murder. Twa Rwandans, though not specifically targeted, were still often victimized in the mass frenzy. The widespread use of machetes in the genocide meant that blood watered the cities and countryside, and survivors virtually everywhere bore the marks of scars and missing limbs. The atrocities also spilled from Rwanda into Burundi, which was also already the scene of violence against Tutsi civilians, especially the young.

Although UN armed forces under General Romeo Dallaire had been in Rwanda at the start of the genocide, the international body had actually prevented them from taking necessary action to stop the violence. Within American diplomatic circles, many prominent figures wholly refused to label the events collectively as genocide, for fear that the UN Genocide Convention would then require a more direct intervention. At the same time, many Western nations took care to recall their own citizens from Rwanda via an emergency airlift. By decade’s end, the American president, William Clinton, visited Rwanda to apologize for not acting to halt the genocide. By then, the damage had been done.

The Rwandan Genocide murdered over two-thirds of the nation’s Tutsis, and as much as 20% of its population. There can be little doubt that the perpetrators felt free to act with impunity in the context of the world’s inaction. The mass killings ended when the Rwandan Patriotic Front seized control, but efforts towards justice would take far longer to progress. A criminal tribunal was established by the UN, and for the first time, rape was officially recognized as a tool of genocide. The work of the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda continues to this day. Also, the Rwandan government has implemented a more traditional justice apparatus, the gacaca courts, in an effort to ease the backlog of cases and bring harmony to the war-torn nation. In these courts, local communities elect a judge to help determine the guilt of alleged perpetrators of genocide. Sentences are lower for perpetrators who can demonstrate a record of repentance and a desire for forgiveness. The goal is that the many perpetrators can eventually be reintegrated into their communities, which is controversial in that it presents a different model from the Nuremberg Trials that followed the Holocaust.

The atrocities in Rwanda highlight several disquieting truths about genocide: that even lifelong neighbors will too often choose to turn against neighbors; that neither gas chambers, nor other sophisticated, modern-day weaponry that places the murderer at physical distance from the victim, are necessarily going to be today’s tools of choice for mass killing; and that, even in an era of greater attention from the mass media to genocidal crimes, most of the world remains slow and reluctant to halt them through any commitment to direct intervention. Even today, terrible acts of violence continue to target Tutsis in nearby Burundi.

The country of Sudan is located in northeastern Africa and is bordered by the Red Sea, Egypt, South Sudan, Central African Republic, Chad, Eritrea, Ethiopia, and Libya. The Darfur region in western Sudan hosts a population of around seven million people.

The tensions in Sudan began following its independence from Great Britain in 1956 when the nation almost immediately became involved in two civil wars for the rest of the twentieth century. Like other post-colonial states, Sudan struggled to guide the direction of the making of the new nation. Competing for limited and scarce resources, different groups took on more extreme positions and tactics. The nomads, made up primarily of groups of Arabs, and the pastoralists, made up primarily of groups of Africans, found themselves in an untenable and impossible conflict, leading to increasingly militarized confrontations. As fertile lands became deserts due to improper agricultural techniques, drought, deforestation, and climate change, famine also plagued the Sudan, heightening the already aggressive relations. When oil was discovered in western Sudan, the government became very interested in the lands of Darfur.

The first civil war ended in 1972, but a second one broke out in 1983. This second civil war, along with famine, displaced nearly four million people and more than two million people died over the next two decades. Despite reports of increasing violence in western Sudan, the government chose not to act in Darfur. Darfur remained underdeveloped and this sense of neglect, marginalization, and inequitable treatment justified, in the minds of rebels, an attack on the Sudanese Air Force Base at El Fasher, North Darfur in February, 2003.

In response, the Sudanese military and groups of government-supported militias known as the Janjaweed (evil men on horseback) have systematically and deliberately attacked villages of the Fur, Zaghawa, and Masalit peoples, who are considered non-Arab and whose individuals made up many of the rebel units. The Janjaweed burned down homes, looted, destroyed natural resources, poisoned water sources, and murdered, tortured, and raped civilians. Janjaweed raids were brutal and cruel, made only more so by the fact that these attacks on the ground were oftentimes coupled with strikes from the air with indiscriminate aerial bombings. The “Darfur Genocide” refers to the mass execution and abuse of Darfuri men, women, and children in the western Sudan that began in 2003. As many as 450,000 people have been killed in these persecutions and over 2,800,000 have been displaced.

Tensions with the bordering states of Chad and the Central African Republic have also been exacerbated as hundred of thousands of Darfuri refugees streamed into the neighboring countries to escape the horrific violence. In July, 2004 the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum declared a Genocide Emergency for the Darfur region of Sudan. On September 9, 2004, United States Secretary of State Colin Powell testified before the Senate Foreign Relations Committee and declared the situation in Darfur a genocide. On February 18, 2006, President George W. Bush called for the number of international troops in Darfur to be doubled. On September 17, 2006, British Prime Minister Tony Blair wrote an open letter to the European Union asking for a unified response to the genocide. In a speech to the General Assembly of the United Nations, the next British Prime Minister Gordon Brown called Darfur “the greatest humanitarian disaster the world faces today.”

In 2008, the United Nations issued a hybrid United Nations-African Union Mission (UNAMID) to maintain peace in Darfur. While 26,000 troops had been authorized to use force to protect civilians, only 9,000 were sent and without the proper equipment and support, they could not complete their mission. On March 4, 2009, the International Criminal Court issued a warrant for the arrest of Sudanese President Omar al-Bashir for crimes against humanity and in July, 2010, a second warrant on charges of genocide. The government expelled international aid organizations that were providing much needed food, medical care, and other services to the displaced communitiesone.

In July, 2011, South Sudan became an independent nation. In July as well, the Liberation and Justice Movement, the umbrella group representing the rebel groups, and the Sudanese government signed the Doha Document for Peace in Darfur (DDPD) that offered a process of peace, although the document has not been fully enforced and implemented.

It was not until April, 2019 that al-Bashir stepped down in response to four months of nationwide protests. Defense Minister Awad Mohamed Ahmed Ibn Auf announced to the nation that al-Bashir had been arrested “in a safe place” and declared a state of emergency for three months.